DU in the High Country

We're headed on a DU-inspired road trip where the air is thinner, but the drive to make a difference is on solid ground.

By Joy Hamilton

Illustrations by Alexandra Cortes (BA ’15)

The University of Denver’s location is a point of pride, and the peaks framing campus are as much of the college experience as cheering on the hockey team and late nights at The Pioneer. Let’s just say, to love DU is to love the Rocky Mountains, and students, faculty and alumni there are shaping the future of Colorado’s high country.

Forecasting the Forests of Tomorrow

Travel with us along the Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway to Echo Lake, where professor Patrick H. Martin's lab is researching how Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir adapt to climate change...

A Tale of Two DU Mayors in Grand County

...aboard the historic Winter Park Express to Grand County, where two alumni and friends are mayors in neighboring towns...

Finding Community in the Rockies

...through winding turns on Red Feather Lakes Road to the Kennedy Mountain Campus, where 4D Peer Mentors welcome DU's newest students...

Bold Flavors, Big Impact: A DU Alum’s Mountain-Made Success

...over Vail Pass to the historic town of Minturn, where one alum has been building community through coffee and tea for 35 years...

Roots in the Rockies: How DU’s Homegrown Social Workers Are Transforming Mountain Communities

...through Glenwood Canyon to the confluence of the Colorado and Roaring Fork rivers, where the Graduate School of Social Work is serving rural mountainous communities...

Walking in Different Worlds

...and across the San Juan Mountains to the Four Corners region where one alumna is guiding students in learning the ins and outs of working in tribal communities.

Along the way, you’ll hear stories of people committed to community and place, tackling challenges like climate change, mental health and housing. Ready to hit the road?

📍 Mount Blue Sky

Forecasting the Forests of Tomorrow

The Martin Lab is discovering how trees adapt to climate change, one seedling at a time.

Trees are nothing if not resilient.

Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir in Colorado’s mountains age well into their hundreds, but to reach the sky, they must survive what are like awkward middle school years as seedlings. This precarious stage is what Patrick H. Martin, biologist and professor in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, and his lab of graduate and undergraduate researchers are most interested in as the West faces prolonged and severe periods of drought.

“Trees can withstand a lot, but these tiny seedlings are often the canary in the coal mine for how things are changing,” says Martin.

Fortunately, the University of Denver’s Mount Blue Sky Station—in operation since 1937—is the perfect natural petri dish for a seedling study. The area’s geomorphology is special due to its alpine glaciers formed during the Pleistocene Epoch—popularly known as the Ice Age—that lasted from 2.5 million to 11,700 years ago. Nearby Echo Lake, for instance, was created by a glacier.

“It’s one of the best parts of Colorado to see traces of how the glacier shaped the surficial geology,” says Martin. “Also being a 14er, it’s a little island of high elevation and one of the largest continuous areas of alpine ecosystem in the Rockies.”

Typically, researchers might drive thousands of miles to reach such an area, but for Martin, it’s just an hour’s drive from his office on campus, a bonus when he accepted the job. But that doesn’t mean the research is a piece of cake.

“It’s not easy to study because forest dynamics can be measured in centuries,” explains Martin. “And how do you study the whole organism when you’re this big and the tree is 40 meters tall?”

Experimenting with seedlings here is fruitful for predicting how climate change will impact forests in the future. Subalpine forests above 10,000 feet like those at the Mount Blue Sky Station have warmed faster than those at lower elevations and have experienced drastic swings in moisture.

Light, shade and survival

Imagine yourself hiking through heavily wooded forest. While it might be one of Colorado’s signature bluebird days, it can be shady and cool on the forest floor. That’s light exposure—a variable the team studied alongside drought conditions.

“We had small gaps where the light is relatively high, and then deeper shade, to see how that interacted with drought stress on the two dominant tree species’ seedlings,” explains Martin.

Their findings showed that one season of reduced rainfall disrupts the survival rate of spruce and fir seedlings. However, the silver lining is that shaded areas help reduce drought stress. “They were droughted for two years, but it didn’t just wipe them all out,” says Martin.

Their research also had a surprising finding related to the two species, or what Martin calls “species-specific stories.” Spruce prefer sunnier spots, so in the shade, their regeneration has less of a chance to succeed compared to fir. The divergence suggests that the forests of today might look different in the future.

“We expect spruce and fir to coexist intimately,” Martin notes, “but you could see drought pushing them in slightly different, more homogenous clusters down the road.”

The findings highlight the importance of considering light and moisture conditions when managing forests to ensure seedlings have the right environment to survive. This could have implications for how humans manage forests to adapt in the face of climate change.

“We’re not going to avoid it altogether,” says Martin, “but a forest manager could take the research and notice spruce is starting to disappear and clear some understory to encourage regeneration.”

A laboratory for the future

It’s obvious when talking with Martin that he’s a tree “stan,” especially for the green giants up near Mount Blue Sky, like Pinus aristata, or the Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine.

“I love the spruce. I love the subalpine forests in Colorado,” he says excitedly. “There’s a couple bristlecone pine trees about 1,600 years old up there.”

But Martin has dedicated his professional life to studying trees for more than just personal reasons. “At first, you do it because you love nature, you love forests, but eventually it will become much more abstract, and the question that drives you is, ‘What’s going to happen with this unprecedented amount of global change?’”

Martin’s study contributes to a growing set of observations that will spread widely among researchers. Colorado learns from what is happening in drier and hotter Arizona, and Arizona in turn learns from Mexico. As drought conditions occur more widely, the East Coast can learn from what is happening in the Western U.S., where conditions are generally more pronounced. “The West is really the laboratory for studying drought,” he says.

Recently, Martin used the findings of the seedling study to help secure a $1.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation. In collaboration with Clemson University, researchers will compare drought dynamics in the Rocky and Great Smoky mountains and determine how tree stress chemistry may indicate whether a tree lives or dies in response to drought.

By “peeking inside a leaf,” using emerging technology called chemical metabolomics, they’ll measure how leaves handle stress in real time, allowing for improved forecasts of forest health under changing conditions. Last summer, Martin and his students began by planting a controlled experimental garden at DU’s Kennedy Mountain Campus, one of the first research projects on the property. Martin expects results within the next five years.

“The garden doesn’t look that exciting yet. But we’re going to have drought shelters, irrigation projects and some shade treatments,” explains Martin. “As far as many ecology projects go, it will look elaborate.”

Until then, the significance of his work already outsizes the seedlings he studies, giving hope that the forests of tomorrow can thrive despite the challenges ahead.

📍 Grand County

A Tale of Two DU Mayors in Grand County

More than 3,800 DU alumni live west of the Continental Divide, and two of them are neighboring mayors and friends who serve the adjacent towns of Fraser and Winter Park.

Brian Cerkvenik (BSBA ’02), mayor of Fraser since 2024, is a Pioneer Leadership Program alum, an avid DU hockey fan and owner of Home James Transportation Services. At 8,183 feet and a population of 1,500, Fraser is known for a vibrant arts scene that helps “keep Fraser funky,” which is the town’s motto.

Nick Kutrumbos (BSBA ’05), mayor of Winter Park since 2020, was raised in Observatory Park near DU, where his mom was a professor. He’s also a hockey fan and owner of the family restaurant Deno’s Mountain Bistro. Home to Colorado’s longest continually operating ski resort, Winter Park has 1,000 residents and more than 3 million visitors a year.

We sat down with Cerkvenik and Kutrumbos to talk about their work in Grand County and how DU prepared them for public service.

What is your proudest achievement as mayor?

Cerkvenik: We’re at a tipping point, where people are moving here and development is booming. We have over 9,000 housing units that are going to be built. To handle that kind of growth, Fraser set up a downtown development authority that will allow the tax increments from property tax to stay within the downtown area so that we can make more improvements to it. We’re also converting the old trailer park in our downtown area into a riverfront district, bringing a walkable area in Fraser that people will want to spend time in.

Kutrumbos: We’ve built a public transportation system from scratch, and the Town of Winter Park owns and operates the regional system serving Grand County. We’ve received grants for electric buses and a maintenance facility that can charge over 20 electric busses. We’re working on a multimodal transportation system which includes rail, bus and fixed cable transit. The town is participating in the Mountain Rail Coalition and supporting the Colorado Department of Transportation and the governor’s office to expand subsidized daily train service to Winter Park and beyond. And we’re working on a gondola less than 100 yards from the train platform that would connect downtown Winter Park to the base of the ski resort.

What is your biggest challenge as mayor?

Cerkvenik: Affordability. People have been priced out. We received a grant through the state’s Department of Local Affairs and the Division of Housing for $3.04 million to purchase 11.3 acres right on the edge of Fraser that is dedicated to affordable workforce housing. Phase 1, including two buildings with a childcare center, begins construction in April. Infrastructure for the entire project, which includes five apartment buildings and 13 for-sale townhomes, is already in the ground.

Kutrumbos: Colorado’s mountain towns generated over $4.4 billion in taxable spending from November 2022 through March 2023, but our communities have very small population bases—so, we get limited state funding to support community housing, sustainability initiatives, state road maintenance, fire mitigation, etc. Over the last 10 years, mountain towns have created coalitions to build political capital at the state and federal levels. Our voices are being heard, but it will always be a challenge to compete for funding with the major metropolitan areas.

How did your DU education prepare you to be mayor?

Cerkvenik: I always had some interest in leadership. I didn’t necessarily think I would get into politics, but when we found ourselves up here in Fraser, that changed pretty quickly. I got on the town board and realized what a big impact it has. Our decisions affect so many more people than just those living in Fraser. The Pioneer Leadership Program had a lot of emphasis on civic roles, and back then I didn’t know if I would use that, but here I am.

Kutrumbos: What’s great about DU is the networking. Being an elected official, it’s all about building relationships, getting out there in the community and talking about these issues that we all face together and finding creative solutions. DU does a great job connecting people.

How do you collaborate with each other?

Cerkvenik: My first thought after moving up here was, “Why do we have these two little towns that are literally right next to each other? Why not combine them?” My attitude has changed in that regard. The two towns have a very different feel and oftentimes different goals. But when we’re looking to accomplish the same thing, it makes a bigger impact to have two towns with a united message. I’m all for Nick’s plan for the gondola and having a neighboring town say, “We also want this to happen,” is helpful. We also share some services to help save our taxpayers money, and we’ve worked together, along with the ski resort, to build a valleywide sustainability plan, which includes everything from environmental sustainability to responsible growth.

Kutrumbos: Winter Park and Fraser are two unique communities that share a municipal boundary that makes it difficult to tell where one town ends and the other one begins. Brian and I meet regularly, and we have a lot of ideas to make our communities a better place to live and raise a family. I am excited to see Brian’s influence on Fraser and look forward to working on collaborative projects.

Most mayors in our resort communities are ski bums that were previously “lifties” (ski lift operators) or bartenders or restauranteurs turned politicians. It’s a benefit to the community because we are accessible. Conversations with constituents are much more productive while chatting with an ice-cold beer or riding a chairlift.

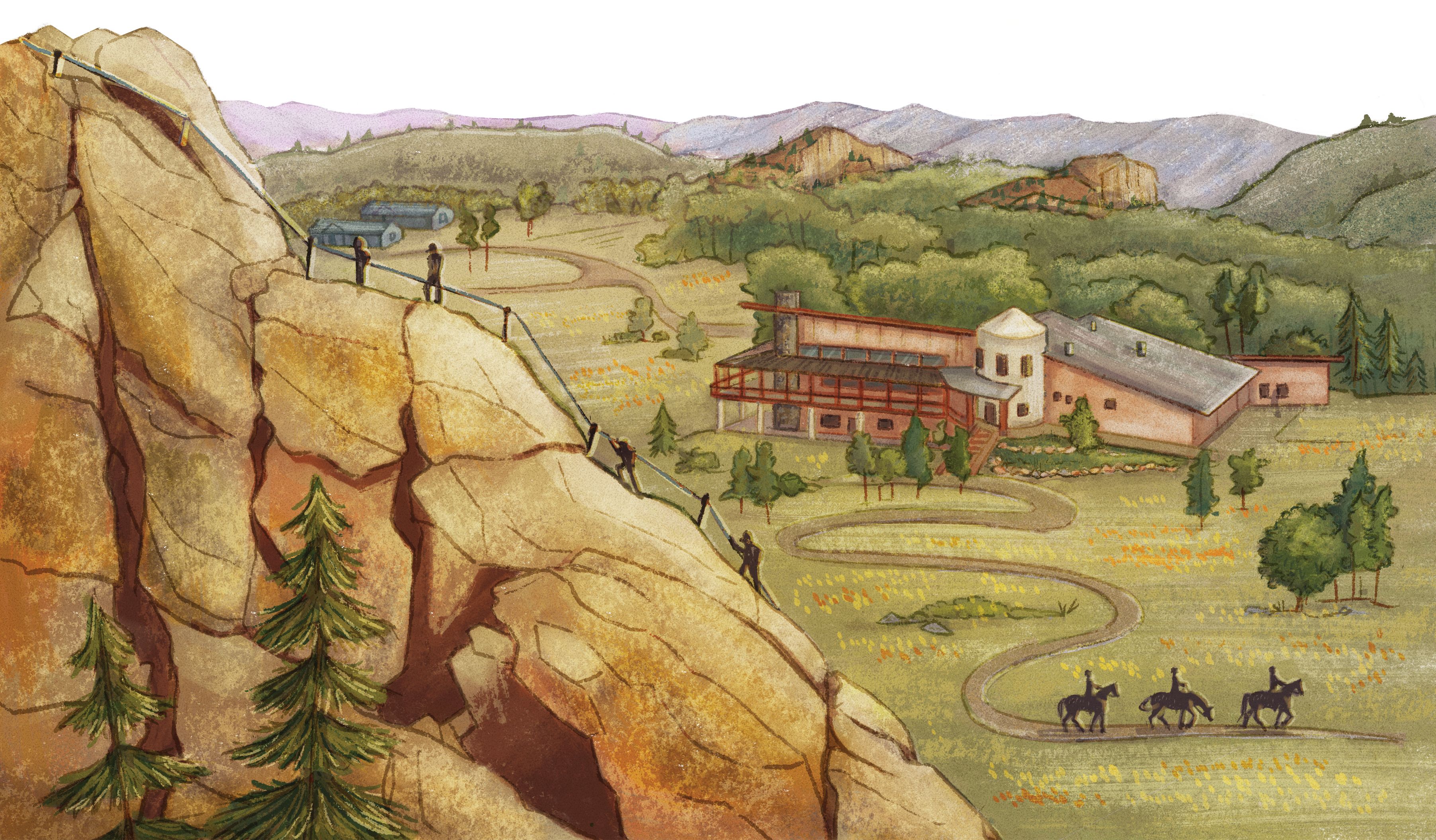

📍 James C. Kennedy Mountain Campus

Finding Community in the Rockies

4D peer mentors create connections and memories under Colorado’s starry skies.

At the James C. Kennedy Mountain Campus (KMC) in northern Colorado’s Arapaho and Roosevelt national forests, 4D Peer Mentors usher in the newest class of DU students during First Ascent, a weekend where undergrads get to know their peers and try quintessential mountain activities like late-night campfires, horseback riding and dangling 50 feet off the ground on a via ferrata.

And the program works—98% of students agreed that their First Ascent experience helped them build new connections, and 95% agreed that First Ascent encouraged them to step out of their comfort zones, thanks to the welcoming atmosphere that their peer mentors create. It’s a student job with the dual perks of getting to be in nature and helping build community.

Here’s what some of the mentors had to say about their time spent at KMC this past year.

“KMC is special, not just because of how you are completely enveloped in breathtaking, untamed wilderness, but because of the amazing team that bonds together to make the First Ascent experience simply incredible on all fronts.”

- Michael Goldstein

“I am able to be present with my friends and peers. I am not stressed about homework and project deadlines. I get to enjoy the beautiful mountains, fresh air and outdoor activities.”

- Aviana Reyes

“My best memory working at KMC was being able to stargaze after my shift.”

- Gus Emerson

“My favorite part is when I’m able to do activities like the via ferrata with students. It’s a daunting couple of hours, but at the end everybody is so excited and proud of themselves. It’s super rewarding to get to say you climbed a mountain, and being there for that excitement is so fun.”

- Robin Bell

“Being outdoors is an essential part of living in Colorado, and not many college campuses give you a taste of activities in that state!”

- Caley Shiflett

📍 Minturn

Bold Flavors, Big Impact: A DU Alum’s Mountain-Made Success

Vail Mountain Coffee & Tea (VMCT) co-founder Craig Arseneau (BSBA ’86) has been waking up the Vail Valley for 35 years. His journey exemplifies how business acumen paired with a drive to make a positive impact can lead to lasting success.

Here’s a look at Arseneau’s story, by the numbers.

8,000 Ft.

VMCT’s coffee is roasted in Minturn, Colorado, at a high altitude in the tradition of Northern Italian roasters, which means sugars and solids caramelize at a slower rate, resulting in sweet, smooth flavors that can’t be reproduced at lower elevations.

105 Miles

Beans and tea travel more than 100 miles from VMCT’s Roastery in Minturn to Beans Café, the student-run coffee shop located in the Fritz Knoebel School of Hospitality Management.

500 Mugs

When Arseneau and co-founder Chris Chantler opened VMCT in 1989, they handed out reusable, branded hot beverage mugs to ski patrollers, “lifties” and restaurant workers, which proved to be a wildly successful promotional tactic.

35 Years

Arseneau and Chantler were traveling in Switzerland in 1989 when they saw the World Skiing Championships broadcast from Vail, prompting them to “get serious” about their entrepreneurial adventure and move back to Colorado from the East Coast to open the Daily Grind Coffee Company in Vail. More than three decades later, they are deeply engrained in the Vail Valley community. “Being avid ambassadors for our community, we’ve unquestionably supported all organizations that have reached out to us for donations or product in kind,” says Arseneau.

32 Women

For nearly a decade, VMCT has financially supported the Colombian Women’s Project by purchasing raw green beans, developing trainings and providing equipment like ecological stovetops and energy generators. VMCT’s program has trained 32 women and 10 men in Colombia, conducted 28 community farm soil analyses and made fertilization recommendations, and given 30 families access to drinking water.

3 Locations

VMCT’s brick-and-mortar locations along I-70 are in Downieville, Minturn and Beaver Creek.

300 Wholesale Clients

If you’ve had a cup of joe in Colorado, chances are you’ve tasted beans roasted by VMCT.

1 DU Family

When Arseneau graduated from DU, he didn’t fully grasp the significance of joining the alumni community—but that quickly changed. His manager at his first postgraduation job in Boston was a DU alum, and now, living in Vail, he actively hosts alumni events and remains connected with the DU network. From longtime friends to new acquaintances, DU’s community continues to shape his experience. “It’s just this family—the DU family—that you don’t know exists when you graduate, but it’s bigger than you think,” he says.

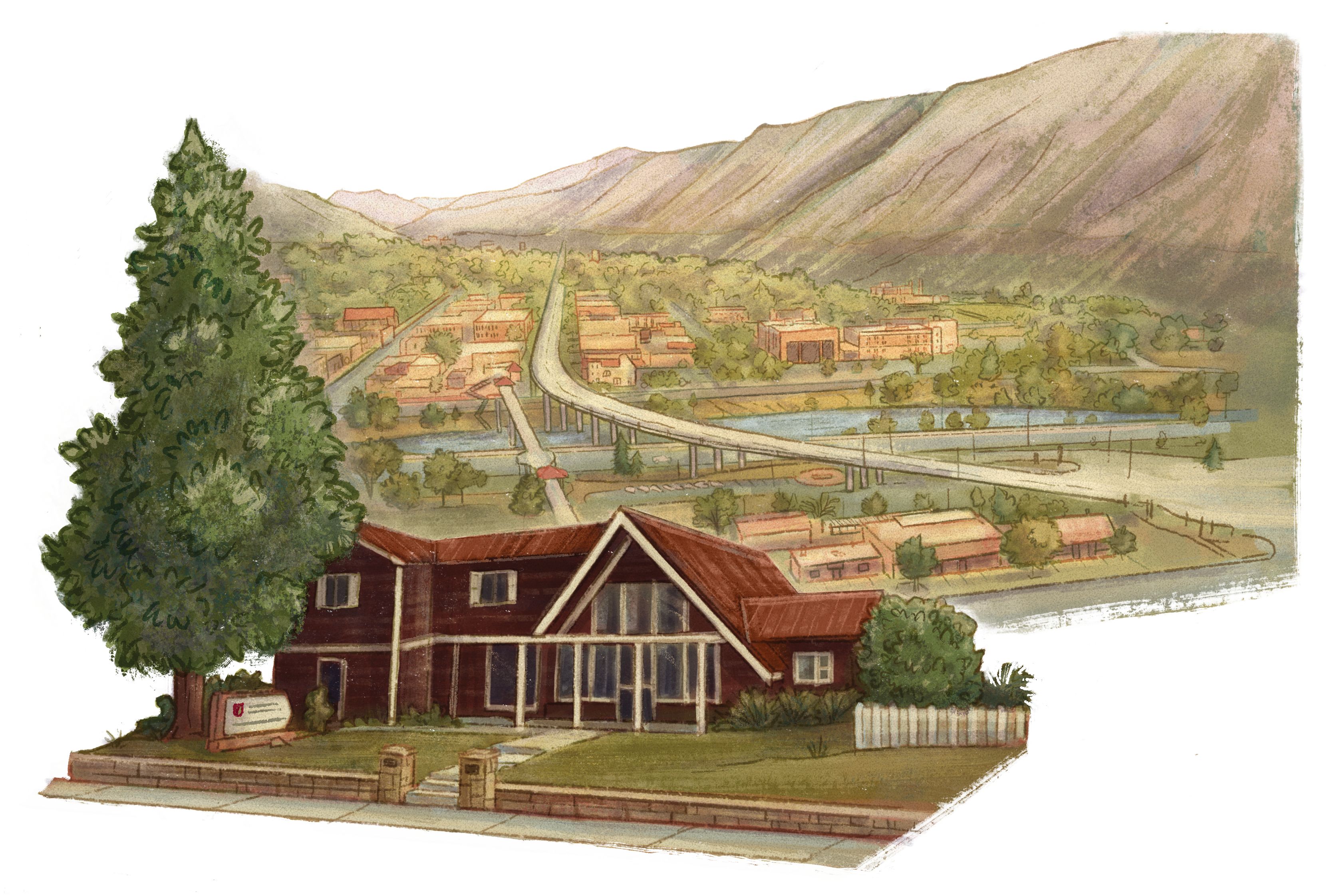

📍 Glenwood Springs

Roots in the Rockies: How DU’s Homegrown Social Workers Are Transforming Mountain Communities

The Graduate School of Social Work’s Western Colorado program is building a formidable local workforce west of the Continental Divide.

Each year, over 1 million visitors travel along Grand Avenue in Glenwood Springs, a four-lane artery linking the historic downtown to I-70 and neighboring mountain towns. Amid this busy stretch stands an unassuming 1970s-style log building with white trim, marked by a sign that reads: “University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work.”

Despite its demure appearance, the program inside is anything but small. Over the past decade, DU’s Western Colorado Master of Social Work (MSW) Program has provided invaluable educational opportunities to rural regions across Colorado—covering Summit, Eagle, Garfield, Pitkin and Mesa counties, areas that make up 87% of the state’s counties experiencing a shortage of mental health professionals.

While the beauty of the surrounding landscape is undeniable, the need the program addresses is immense. Its superpower is preparing local students to understand and serve in diverse rural contexts. From schools and hospitals to clinics, rehabilitation centers, veteran’s affairs offices, hospice centers and youth counseling services, nearly every sector has ties to DU, a testament to the growing web of skilled workers the program has produced.

Students commute—sometimes for hours, in rain, snow, sleet or shine—every Friday to Glenwood Springs for classes, then spread out across the region for field education during the week. With a nearly 100% completion rate, graduates have rolled up their sleeves and helped to transform the regional social work landscape, building a network that is vital to the well-being and future of rural communities in Western Colorado.

In the community, for the community

Rachel Forbes, program director for the Western Colorado program, spent her first day on the job in 2013 building the program’s home base on Grand Avenue from scratch, ripping open IKEA boxes and tediously tightening screws. Her willingness to dive right in and get the job done exemplifies the program’s overall ethos and reputation.

Its decade-long success and support in the region stems from adapting to community needs, says Forbes, who spent countless hours on mountain roads cultivating relationships with regional partners when she started her position.

“We wanted the curriculum to be community-informed,” she says. “Somebody would say, ‘There’s an opioid crisis, and we don’t have enough clinicians who understand that practice area. It would be awesome if you could train your students in substance use and misuse disorders.’”

In turn, Forbes has kept the program responsive and relevant. Students have logged more than 100,000 field education hours at local organizations, planting the seeds for not only post-graduation career paths but also a pipeline of skilled workers ready to enter a talent- thirsty workforce.

“You can have all the academic training. You can read all the articles. But unless you’re able to transfer what you’re learning in the classroom into real-world scenarios with messy humans, nothing is going to make sense to the student,” says Jarid Rollins, a licensed clinical social worker at MidValley Family Practice in Basalt and adjunct instructor who has supervised several DU students.

Rollins says DU students have an exceptional level of passion and commitment, due to the quality of the students the program attracts. Cohorts are diverse, with students ranging from those in their early 20s to mid-career changers in their 50s, each bringing distinctive cultural and professional experiences.

“It feels like a collection of interesting and dynamic human beings coming together with very open hearts, trying to do our best to learn how to be helpful in our communities,” says Renee Prince, a current MSW student who chose the program during a career change because of its in-person learning.

For those who were born and raised in the area, the educational opportunity is especially meaningful. Cristina Andrade Guzman’s (MSW ’19) story has come full circle: She was a patient at Mountain Family Health Centers and has worked there as a licensed clinical social worker for the past six years.

“Growing up in this community, I always knew that I wanted to give back because my community gave back to me,” she says.

It wasn’t until she started the program that she realized the immense gap her work would fill, especially for Spanish-speaking clients, who make up 90% of her clientele. Andrade, who is bilingual in English and Spanish, is in high demand, and she’s risen to the occasion by working alongside medical and dental providers.

Though working with clients experiencing depression, anxiety, trauma, grief, chronic health issues, addiction and more can be draining, the reward for Andrade is witnessing the immediate impact her work has on her clients.

“You can see clients learning positive coping skills to help with whatever they’re going through, and over time, they get better. That progress is what has kept me going,” she says.

Retiring an old stereotype

For alumna Yesenia Silva Estrada (MSW ’17), the stereotype of an overworked social worker coming to take your child away is both tired and limiting when describing the impact MSWs have made in the Rocky Mountain region.

Silva Estrada, now the vice president of planning and chief of staff at Colorado Mountain College (CMC), explains that many people mistakenly believe social workers only assist low-income clients as part of a system focused solely on poverty. In practice, social workers are where you wouldn’t expect, addressing complex issues at a bird’s eye view by coordinating services in the area or using systems thinking to address root causes.

“We are all over the place. We are in big organizations, we're doing direct service to variety of different individuals, we're also planning programs, and we're directors of programs,” says Silva Estrada. “We're in very different places and spaces creating change.”

A fellow student from Silva Estrada’s cohort, Barbra Corcoran (MSW ’15), represents another non-stereotypical role as an integrated behavioral health provider at Valley View Hospital. Providers like Corcoran feel that if they can bring behavioral care into approachable and more affordable healthcare settings as opposed to siloed clinics, they will reach more people with the care they need.

“The goal is that we just meet people when they're in a moment of need and take the pressure off of primary care providers,” she says, “Then we get to work as a team to support that patient.”

DU’s program confirmed what Corcoran had observed as a licensed clinical social worker and addiction counselor: that life circumstances or experiences can have negative or positive outcomes on individuals. Social determinants of health can include stressors like transportation, housing, food and safety in one’s home. These stressors are intensified on the Western Slope, with long distances to services and a housing supply that competes with second home buyers and vacation rentals.

Paradise paradox

The mountainous regions where students and graduates serve exist in what Silva Estrada calls the “paradise paradox.”

“It’s beautiful to live here. It’s known for the outdoors, but statistically, we have a high rate of suicides, a high rate of mental health crisis and challenges that are exacerbated with the high cost of living,” she notes.

Therefore, how issues are addressed in rural areas can be different from their urban counterparts. “You can’t take an urban intervention or program and just plop it into a rural area. It has to look slightly different, sometimes significantly different,” says Cristina Gair, director of West Mountain Regional Health Alliance, one of the programs crucial to establishing DU’s presence in the community.

The “paradise paradox” is most obvious in the housing crisis, which hits rural communities hardest due to limited inventory and competition with second-home buyers. This issue permeates all aspects of life, shaping the future direction of the program’s curriculum and focus.

“The number of times I’ve heard a client say something like, ‘I don’t feel accepted by this valley’ because of their housing situation is more than a dozen times in the last two years,” says Rollins. “That feeling of disconnection and disenfranchisement from our communities is driven by the housing crisis, in some respects.”

To address the housing crisis, the Western Colorado program and its collaborators are working to harness the work done by the Graduate School of Social Work’s Center for Housing and Homelessness Research, led by Professor Daniel Brisson.

Another issue that’s unique to the area is the lack of lawyers representing plaintiffs in employment cases, making it what’s known as a “legal desert.” Lindsay Fallon (MSW ’15) received her degree on the Denver campus and, after running programming in Denver with Towards Justice, a nonprofit law firm that represents low-wage workers, she moved to Glenwood Springs to expand the program’s presence in the western part of the state.

Fallon has witnessed employers in the region blacklist and retaliate against workers who speak up about workplace safety or wage and hour violations. These intimidation tactics have an especially harmful impact on mountain town workers, where job opportunities are scarcer than in urban areas, she says. As a result, many employees stay silent, fearing retribution. Her goal is to level the playing field for workers.

“My hope is that workers—the lifeblood of our communities—have the kinds of protections and legal support to ensure that their participation in our economies is sustainable and dignified,” says Fallon. “We live in a community with considerable inequity. This is a problem that won’t go away without a continued fight.”

The close-knit nature of these communities can be a double-edged sword for social workers, too. Everyday tasks like grocery shopping or attending social events can be challenging when clients are around. At the same time, providing care locally and creating a sense of togetherness helps sustain a thriving workforce in a place they call home, and where millions vacation.

The long game

In rural communities, collaboration isn’t a buzzword for a LinkedIn post; it’s a necessary foundation for any successful initiative.

“This valley gets smaller and smaller the longer that you live here,” says Forbes. “People tend to play the long game and invest in relationships over time, which is important to building the social fabric of a place.”

That’s why DU’s program is building relationships with CMC and Colorado Mesa University to create a pipeline of MSW students. They’re also reaching out to high schools, telling students about the varied career paths a degree in social work can offer, with a particular emphasis on recruiting bilingual students.

The program’s leaders and graduates share a sense of accountability to their rural communities, driven by the desire to build more resilient towns through a legion of changemakers. Neighborly accountability shapes the program’s impact and ensures its future success. Students enroll not just for a degree but to care for the communities they call home.

“Just imagine if this program was not in existence,” says Gair. “There would be approximately 100 fewer people in the workforce. It’s been a game changer for this region.”

The frameworks and skills they’ve gained from the program are crucial to creating the world they envision: one that is compassionate and just and helps those in need. Although 100 graduates might not seem like a lot to urbanites, the ripple effect is transforming Colorado’s mountain communities from the inside out.

“Our profession is called to be in the service of others, to see everyone with dignity and worth, and to see them in their environment without judgment,” says Silva Estrada. “Imagine the type of community and environment that could bring in a world that’s super divisive right now.”

📍 Durango

Walking in Different Worlds

DU’s Four Corners Master of Social Work program director and alumna Janelle Doughty (MSW ’04) equips students to navigate the complexities of working in tribal communities.

When Janelle Doughty mentors students passionate about social work, she encourages them to “walk in different worlds”—a challenge to understand, navigate and advocate for cultures different from their own. As an enrolled member of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and Navajo from the Red Running in the Water Clan, it’s something she does daily—maneuvering between different Indigenous communities and the predominantly non-Indigenous world.

A problem solver

Doughty, a graduate of DU’s first Four Corners MSW cohort in Durango in 2004, became its director 15 years later, using her expertise to guide students in caring for Native communities. Prior to joining DU, Doughty spent decades using her social work background to navigate the complexities of tribal and federal systems.

A relentless problem solver who asks the right questions, she worked with the federal government to create processes for prosecuting non-Native criminals on tribal lands. Collaborating with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Denver, she helped establish a system to cross-deputize tribal police officers, allowing them to make arrests on both the reservation and federal lands. Her work was so instrumental that she testified before the Committee on Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.

“It was fun getting out of my little tribal bubble and onto a national level,” she says, “to get other U.S. attorneys that have Indian Country in their districts to work with those tribes so their tribal police will have the ability to arrest and move those cases to the federal system.”

Then, as the director of the Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribe’s Social Services Department, she supported Ute Mountain Ute youth who were in Denver residential treatment facilities. When she learned that the Colorado Board of Education did not recognize the non-accredited diploma that they and non-tribal students received in treatment, she worked with the local board of education to come up with a way to test the tribal youth that allowed them to receive an accredited high school diploma.

In 2009, she was appointed to a three-year term on the Colorado Commission on Civil Rights by Gov. Bill Ritter. Given that experience and her extensive work with tribal communities, Doughty now tailors the Four Corners program to serve Native practitioners and communities throughout the region and beyond, including students coming from places like Oklahoma or Alaska.

Bridging cultures

The Four Corners program, which has local field education in Jicarilla Apache, Navajo Nation, Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute nations, offers several courses specific to Native American contexts. They include policy related to historical issues like boarding schools; federal policies on the environment; cross-cultural values in Indigenous communities; and a 10-day immersion course on the Southern Ute, Ute Mountain Ute and Navajo reservations.

Doughty ensures course content is relevant to all students—the 25% of students who are Indigenous as well as non-Native students planning to work in tribal communities. In addition, a third of the course includes material related to rural social work and working with Indigenous communities.

“I talk about walking in different worlds. These tribes are very different. We’re not similar to each other,” says Doughty. “For folks coming in, I really want them to understand their role as they walk.”

To help faculty who may not have the background knowledge to incorporate relevant material, Doughty draws upon the Four Corners Native advisory board and her own network cultivated by decades in social work, bringing in tribal leaders, prosecutors, tribal enrollment experts, public defenders and health care professionals.

Reflecting on her journey of navigating multiple worlds, both personally and professionally, Doughty embraces her ability to be a bridge between different environments and communities.

“The Ute people were warriors. We are people that are very direct. We are people that want to know what’s going on and ask direct questions,” explains Doughty. “The Navajo side of me has to remember that I cannot ask directly because it’s rude to do that. I have to talk around the issue before I get to it. It’s a belief system of being balanced and in harmony.”

In the classroom, Doughty asks students to practice cultural awareness in a controlled setting before engaging in field education. She has created a space where students can be candid, ask questions and feel safe. Specifically, she wants non-Native students to understand themselves and their motivations as well as the importance of tribal sovereignty before working with clients.

“I tell them this is a place where I’d like for you to make the mistakes,” says Doughty. “Let’s do this in the classroom, because you could do a lot more harm coming into a community or culture you don’t understand.”