All Access Pass: The Newman Center

Hours before the performers take the stage, a different cast of characters are working tirelessly to give the audience the world-class performance they came for.

By Emma Atkinson

Photography by Wayne Armstrong

Not all the magic happens on stage at the Newman Center for the Performing Arts. There’s an intricate dance, a carefully choreographed series of events behind the scenes that must fall into place before the curtains rise.

As the daughter of a stage actress, I’m no stranger to what happens backstage before a show—but what I saw during an afternoon at the Newman Center helped me see the hard work that goes into these productions with fresh eyes.

While behind the velvet curtain often looks the same, no two theaters ever feel the same, and that’s because of the people who work there.

Meeting the Guys

It’s 1:30 in the afternoon, and by the time I arrive backstage at Gates Concert Hall, the guys have already been there for at least an hour.

By “guys,” I mean a troupe of lighting and sound experts, all dressed in black, who are busying themselves with their respective pre-show tasks—taping down wires, setting up microphones and instruments and chairs. The expansive stage floor, also black, is bathed in lavender and gold light. Seven black microphone stands and a dozen equipment trunks are positioned adjacent to one another, a skeleton of a performance setup.

Everything is black, black, black, meant to blend in, not take away from the performers—who, on this night, will be blues and soul singer Martha Redbone and her band. They’re the stars of the show, after all. But the performers won’t be here for several hours, and there’s much work to be done by the unseen stars of the backstage.

These guys—the stagehands and lighting coordinators and sound specialists—are dedicated to their work. You have to be, to give up your nights and weekends like they do.

Shakeel Wahab sits off to the side on stage left—the left side of the stage from the performer’s point of view—fiddling with what looks like a large laptop computer.

It’s not actually a computer, though, Wahab tells me. It’s called a stage monitor, and it allows him to control what the performers hear. This evening’s performers will each have a small speaker in front of them—only the performers themselves can hear what comes through these speakers, and Wahab controls all of them.

“You gotta learn the baseball signals,” Wahab says. “Like this means turn the voice up.” He makes an upward pointing gesture with his hand.

I ask if there are standard gestures all performers use.

“No, they all have their own signals,” he says. “Sometimes I’m like, ‘What does that mean?’” He shrugs and laughs, but it’s clear that the signals are an integral part of the song and dance—literally.

Wahab, the operations coordinator, is 65. He’s been with the Newman Center for 15 years but has been in the industry for 40. He worked with comedian Steven Wright, serving as his tour manager for several years.

“Everybody was jealous that I got to tour with a comedian,” he remembers, laughing. Wahab’s peers in the industry always complained about how much time it took to set up for their respective performers, but Wahab couldn’t relate: “They’d ask, ‘How much setup time do you have?’ I was like, ‘An hour.’”

I tell him it seems like he’s lived many lives.

“I have lived quite a few,” he replies with a smile.

In the background, other members of the crew are setting up pieces of equipment on stage. There’s a print-out of a map of sorts that depicts where each instrument, speaker and microphone should go. Every visiting performer provides one of these maps; they’re sort of like the Bible of pre-show stagehand work.

George Kallivrousis, a part-time stagehand, shows me how they’re setting up the gleaming black piano.

“Because the piano is such a huge instrument, we usually like to get one mic on the lower notes, one mic on the higher strings,” he says. “And then if you want to get real fancy, you can put, like, four mics in there.”

Everyone is pretty relaxed. Wahab, whistling a casual, unidentifiable tune, gets up from his chair next to the stage monitor to stretch his legs. Someone has bought a couple sodas, and Wahab cracks one open.

“I needed this Pepsi-Cola,” he says, taking a long sip.

Several of the guys describe this backstage work as “the calm before the storm.” They’ve done this before—some of them hundreds of times—and they know the drill.

Lighting the Way

The Robert and Judi Newman Center for the Performing Arts at the University of Denver opened its doors in 2002 and is now known as one of the premier performing arts venues in Denver—and the nation.

June Swaner Gates Concert Hall, the Newman Center’s largest venue, was designed to resemble an elegant European opera house and is home to hundreds of events and performances each year. With a professional-size stage, orchestra pit and fly tower, Gates Concert Hall hosts dancers, singers, symphonies, graduation ceremonies, and more.

At this point in the afternoon, the seats of the hall are empty, the red velvet seats reflecting the muted colors of the stage lights. The crew tinkers with equipment, calling out to one another and speaking into radios as they adjust, test and adjust again.

I head up to the lighting booth at the very back of the theater, where I meet Zach Jovanovich, the lighting director. He’s been with DU for 11 years.

A former biology student-turned-theatre major, Jovanovich says something clicked for him when he took a required stage tech class in college. He’s “good with his hands,” he says, so he moved away from acting and turned to the art of backstage work.

The booth is small and dimly lit, but Jovanovich turns on the overhead light for me. Bathed in fluorescence is a large switchboard and two screens. There are probably at least a hundred buttons and switches, and they all do something different, from spotlights to backlights and more. Everything lighting-related that happens during the show happens at the hands of Jovanovich.

Jovanovich is currently on his radio speaking with Thomas Bolton, a crewmember who has climbed to the ceiling of the theater to adjust some of the larger spotlights by hand.

“Thomas, let me know when you’re up there and comfortable,” he says.

Thomas responds affirmatively.

“Just let me know and I'll take some of these lights down on the stage,” Jovanovich says into the radio.

Part of his job, he says, is to direct the crew to set up lights that are complimentary to the performance and to the artists on stage.

“So, what we're doing now—we're about to do a focus, which means we're just pointing the lights where they need to be, and we're making sure they have the right color filters in them,” Jovanovich says.

Jovanovich says his standards are the same no matter the event or performance—he could be lighting a high school graduation or a John Legend show and his work would be the same. While the quality of his work remains consistent, no two shows are the same when it comes to lighting. His first job is to work with the performers to figure out what kind of lighting they want.

“Sometimes the performance is static; they stay in one spot,” Jovanovich says. “So, for the musicians, they’re probably gonna stick by their instruments. If it was a dance show, then we would have to light the whole stage. Some artists are very specific: ‘We want this song to be this way, and we want this to happen at this time.’ And so, it really depends on the performance.”

“We're presenting a product, right? So, we want that experience, for both the artists and for the patron, to be world-class,” he says.

Watching the stage, Jovanovich taps a button and the board lights up. He taps again and the lights on stage dim, revealing a single spotlight.

Jovanovich compares the delicate dance of stagehand work to a delicious Louisiana seafood dish.

“I don't know if you cook, but it's like a gumbo,” he says to me, smiling at the analogy. “You put everything in the stew, and you make your roux, and you put in the meat; it won't taste right until it simmers and comes together, right? Once it comes together and you have a thousand people who are just jazzed to be here, they get an experience they'll remember for years, maybe a lifetime, and I was a small part of that.”

Jovanovich has another clever comparison to make.

“I often say that being a stagehand is like being a pirate,” he says. “Usually it's atypical personalities, you wear all black, you have tattoos. You can swear, you pull on ropes.”

I laugh, and he does too. “It's very, very much in the nautical tradition.”

Checking the Sound

After I’ve finished up with Jovanovich in the lighting booth, it’s already time for sound check. I sit in the very back row of the dark theater as Martha Redbone and her band take the stage.

She’s dressed casually in jeans and a button-down shirt, a little black purse slung across her body. It’s an otherwise muted palette that stands out against the all-black of the crew. Redbone is accompanied by five musicians—a drummer, a pianist, violinist, guitar player and a bass player.

Redbone carries a tall wooden stool and a black music stand to the front of the stage and sits down, the band tuning up behind her. The violinist smiles as he chalks his strings, a cloud of dust rising around him. The pianist clinks out a few soulful notes and the violinist plays along.

Everything on stage is much the same as it was earlier in the day—but all the chairs, speakers and microphones have been moved much closer together. It’s organized and intimate, and the band members chat quietly amongst themselves as Redbone tests the microphone.

“Mama loves me, she told me so,” Redbone sings, her voice rich and words slow.

She belts a higher note and turns back to her pianist to check if she’s in tune: “Is that right, Aaron?” He nods in affirmation.

“Check, check, check, one, two, one, two,” she sings playfully.

The violinist bows a bluegrass tune, and Redbone hops up from her stool and dances a little jig, laughing. At Redbone’s signaling, the band starts up. They play, and each musician starts to signal to Wahab, who’s stationed just out of sight backstage, to turn their speakers and amps up or down.

The Unsung Heroes of Newman

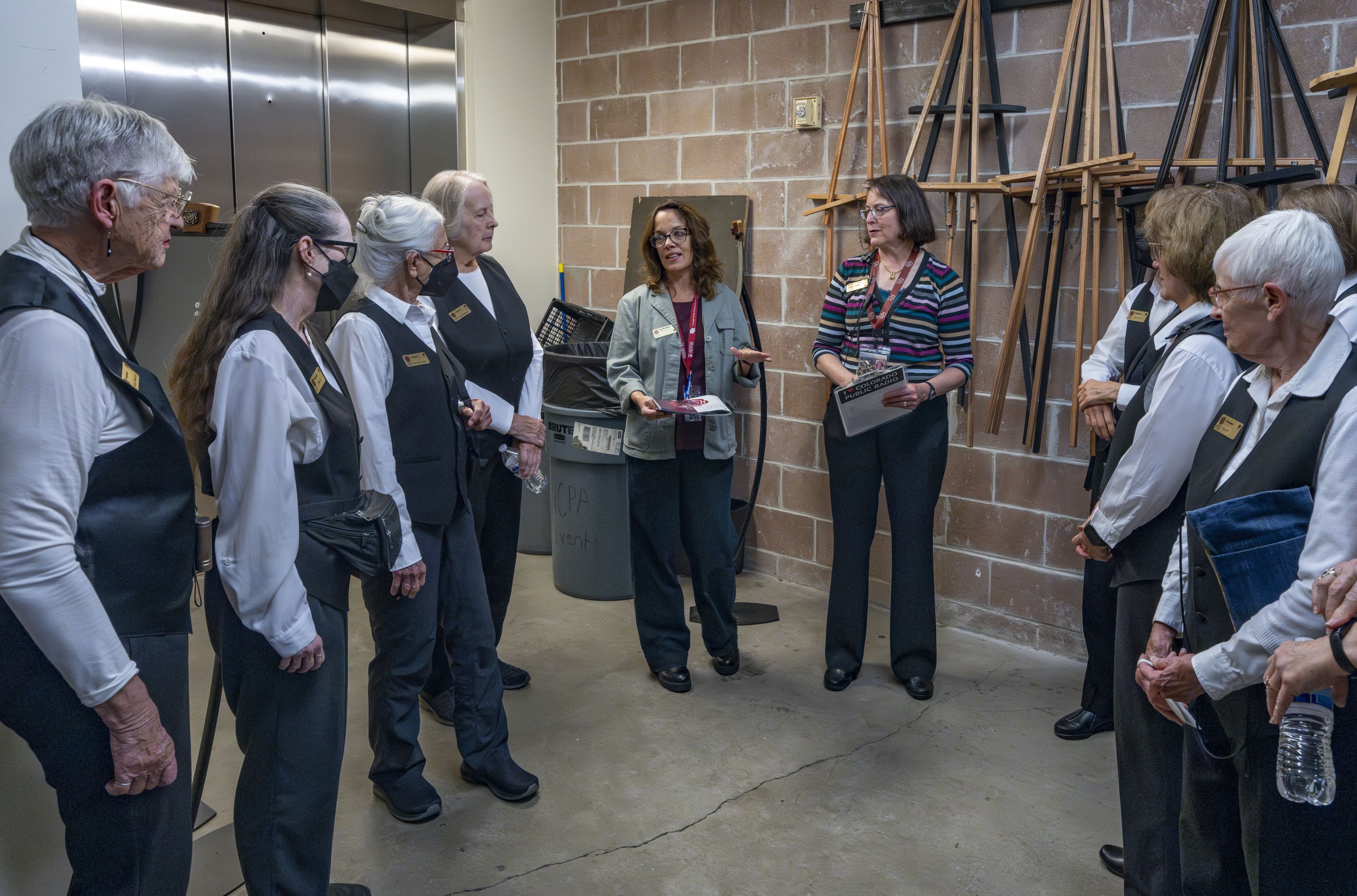

While the sound check carries on in the theater, there’s much commotion out in the lobby—a band of ushers, dressed in black vests and pants and white shirts, are gathered and awaiting instructions.

They’re mostly older women, retirees who live near the Newman Center or have some connection to the University.

Susan started ushering at Newman at the end of 2020. She calls herself an “arts junkie,” and she’s got the numbers to back it up—she ushered a record 56 shows at the Newman Center in 2023.

“I keep track of how many performances I do, and, of course, they're varied,” she says. “We have dance schools that come in, we have memorial services held here, we have all kinds of events that take place here.”

Tracy has been ushering since 2015—and she’s got thoughts about her outfit.

“I call it the penguin suit,” she says.

The ushers go through yearly training where they learn about safety plans and the code of conduct. And before every show, they “huddle up” to learn about that particular performance.

“It's really about helping people, showing people around, enhancing their experience,” Tracy says.

Tracy says her favorite performances are the ones where she interacts with people who might not normally be patrons of the arts.

“One of the biggest joys that I have had is when there is some sort of an outreach performance, and you're getting people who are not the season ticket holders, who are not familiar with the venue, and making sure that they know that they are welcome, that they feel like they learn a little bit about how to get around, and that they are going to feel like this was a good place to come and they'll want to come back,” she says.

As I finish speaking with Tracy and Susan, the head usher starts rounding everyone up for the huddle.

Wahab and his crew are ready backstage. Jovanovich is on lights, which are still dim on stage. Redbone and her band are warmed up and waiting in the green room. People are starting to mill into the lobby, dressed nicely for a night out.

A voice comes on over the loudspeaker: “Ushers, open the house.”

It's showtime.